Places to Roadside Camp in Early Spring in Adirondacks

The two longest back country roads in Adirondacks — Cedar River-Limekiln Lake Road and Piseco-Powley Road — are generally closed during mud season. Other dirt roads like Moose Club Way tend to be muddy, and their is a risk you’ll get stuck back there.

It’s always a good idea to bring extra weight in your truck bed, a come-a-long or whinch, and snow shovel. You might not be far from a blacktop road at these campsites, but that is no guarantee you won’t get stuck.

1) NY Route 8 / East Branch of Sacandaga River

The campsites are all off NY 8, an all season plowed and maintained asphalt road. Some sites are reinforced with gravel. Be aware some sites may be plowed full of snow from the winter clearing of NY 8. Roughly 15 campsites along this road, however some may be too muddy for this time of year.

2) South of Arietta Town Line on Piseco-Powley Road

There are 7 campsites along Piseco-Powley Road, north of Stratford, prior to the Arietta Town Line gate, which is near the Potholers on East Canada Creek. This road is well packed dirt, reinforced with gravel up to gate, and should be accessiable year round, minus the snow.

3) NY 421 at Horseshoe Lake

NY 421 is an asphalt road, and there are 4 campsites prior to the gates for Horseshoe Lake Road and Lows Lower Dam Road. These gates will be closed, but the sites along NY 421 before the asphalt runs out should be good as long the snow is off of NY 421..

4) Mountain Pond

Mountain Pond Campsites are on an old routing of NY 30. While now unplowed in the winter, the road is mostly hard asphalt, asphalt chips, and gravel. Many of the campsites are reinforced with gravel, but be careful with some of the sites.

5) First Campsite on Wolf Lake Road.

There is a campsite on Wolf Lake Road, right before the parking area and winter road gate for Wolf Lake Road Extension. This campsite is grass, however if it’s relatively dry, snow and mud free, this is possiblity.

6) Reeds Pond Campsite.

Before the black top runs out, there is a campsite along Reeds Pond, which is nice for it’s solitude, but nearness to a dirt road. The campsite may be muddy, depending on the conditions.

Roadside Campsites I’ve Camped in Northern Adirondacks

North West

Streeter Lake Road

- Campsites are nice

- Many campsites are close to road

- Road is an old railroad bed

- Streeter Lake and Mud Pond are nice paddling, but a little small and with beaver dams

North Central

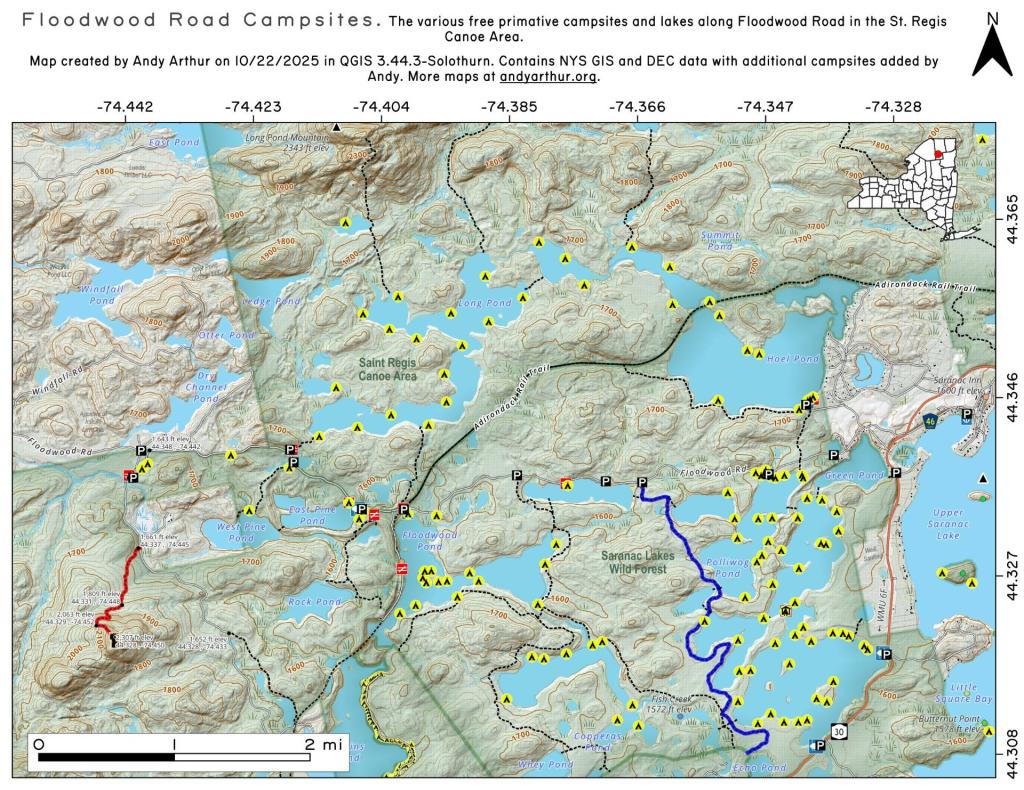

Floodwood Road

- Often crowded, hard to get a roadside campsite some nights

- Campsites are clustered close together

- High enforcement precence

Jones Pond

- Campsites are quite nice, but only 5 campsites and 3 tent sites

- Road noise from nearby roads

- Lake is larger then Mountain Pond

- Nearby is the drive-in campsites along north-western portion of Rainbow Lake (not to be confused with Bucks Pond State Campground)

Mountain Pond

- Close to St Regis Canoe Area (10 miles south)

- Quieter compared to busy canoe area

- Located on an Old Routing of NY 30

- Conviently located to Paul Smiths and NY 30 corridor

North East

Union Falls Pond

- A group of undesigned drive-in campsites along northeastern section of Union Falls Pond, shown on DEC maps

- Across the way from a private campground

- Union Falls Pond is large, can be choppy from the wind

- Great views of Whiteface and other high peaks from the campsite.

North-Central Central

Horsehoe Lake

- Horsehoe Lake has several campsites along, as does the dirt road beyond it for a ways.

- The best roadside campsites go fast on the lake, but you can always camp on the less desirable campsites, then check out Bog River Flow, and tent camp up there.

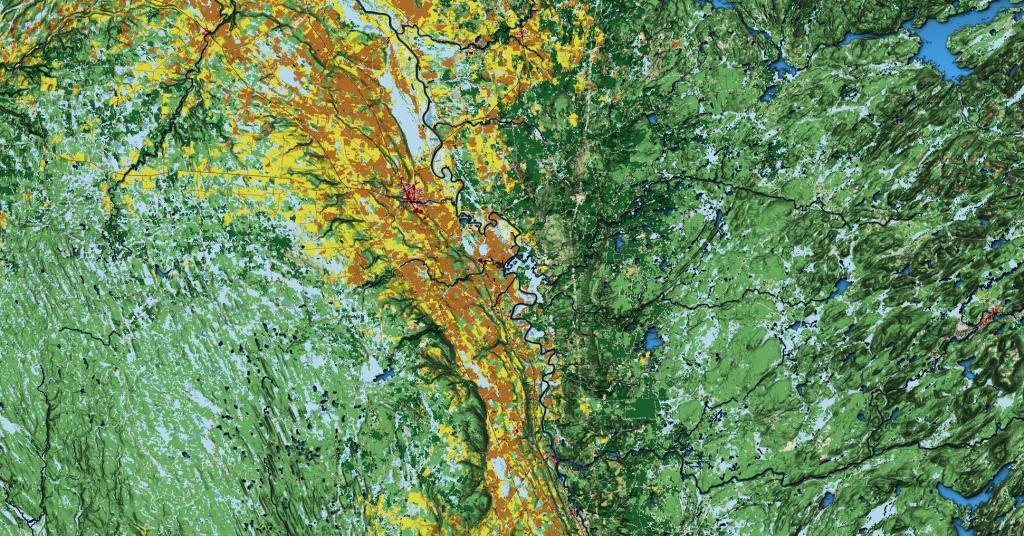

Adirondack Park State Land Acquistion Policy

Today’s fodder is based on the text of as Adirondack Park Land Acqusition Policy, as described in the Adirondack Park State Land Master Plan. I added the headings and pictures to make it more readable. — Andy

The Agency has an important interest inr future state land acquisitions since they can vitally affect both private and public land within the Adirondack Park. As a result the Agency recommends that the following guidelines should govern future acquisitions of state lands within the Park…

State Should Only Acquire

Adirondack Park Land for Forest Preseve.

1. Future state acquisitions within the Adirondack Park should generally be restricted to the acquisition of forest preserve lands. Where special state purposes are such that non-forest preserve land might be acquired (if such acquisitions are constitutionally permissible) the amount acquired for other than forest preserve purposes should be kept to the minimum necessary. Thus, should the state acquire a 100-acre tract on which it wished to place a hospital, a prison, an office building or another facility only that part of the tract, say twenty-five acres, that is actually necessary for the facility should be classified as non-forest preserve.

Reasons Not To Acquire Land.

2. As a general guideline, the state should avoid acquiring lands for non-forest preserve purposes (if such acquisitions are constitutionally permissible) within the Park where:

— the tract is not contiguous to a public highway; or,

— the tract is of a native forest character, i.e., stocked with any size, native tree species with twenty-five percent crown cover (plantations are not considered to be native forest land); or,

— the tract involved consists of more than 150 acres; or,

— the tract is contiguous to existing forest preserve land; or,

— the tract is within one-half mile of a block of forest preserve land of over 1,000 acres; or,

— the tract lies at an elevation greater than 2,500 feet; or,

— the proposed use of the tract will materially alter the surrounding environment; or,

— the tract is of significant scenic, ecological or geologic value or interest.

New Intensive Uses Should Be Restricted

to Private Companies and Individuals.

3. Save for (i) the two existing alpine skiing centers at Whiteface and Gore mountains and the Mt. Van Hoevenberg area; (ii) rustic state campsites, a long accepted intensive use of the forest preserve; (iii) visitor information centers, memorial highways, beaches and boat launching sites; and (iv) historic areas (guidelines for which are provided elsewhere in this master plan), the state should rely on private enterprise to develop intensive recreational facilities on private lands within the Park, to the extent that the character of these lands permits this type of development, and should not acquire lands for these purposes.

Lands Most Desirable to Add to Forest Preserve.

4. Highest priority should be given to acquiring fee title to, fee title subject to a term of life tenancy, or conservation easements providing public use or value or rights of first refusal over,

(i) key parcels of private land, the use or development of which could adversely affect the integrity of vital tracts of state land, particularly wilderness, primitive and canoe areas and

(ii) key parcels which would permit the upgrading of primitive areas to wilderness areas.

Preference for Consolidation of State Parcels of Land.

5. High priority should also be given to acquisitions of fee title which permit the consolidation of scattered tracts of state land.

Protection of Deer Wintering Habitats.

6. Fee title or appropriate conservation easements should also be acquired to protect critical wildlife areas such as deer wintering areas, wetlands, habitats of rare or endangered species or other areas of unique value, such as lands bordering or providing access to classified or proposed wild, scenic and recreational rivers.

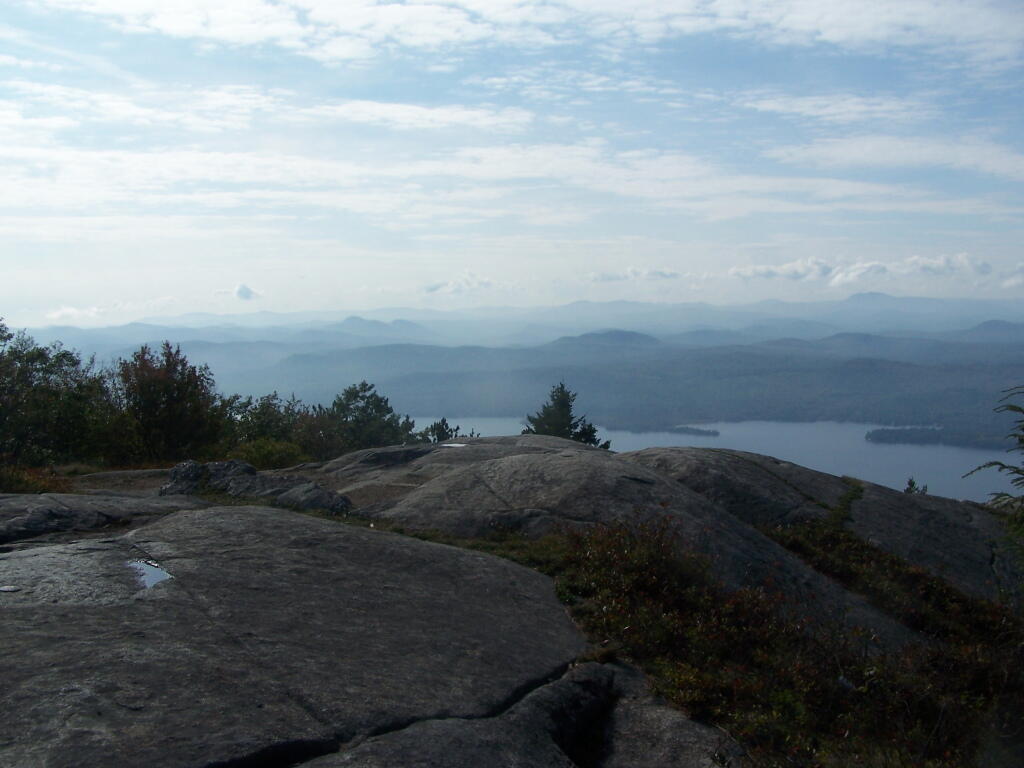

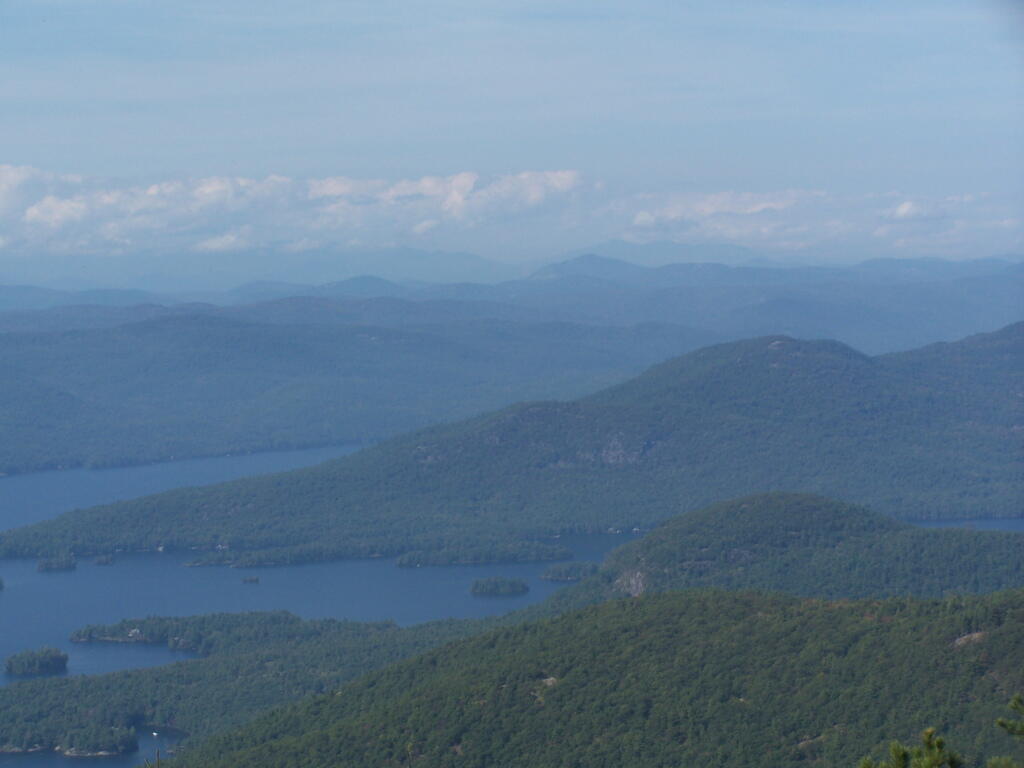

Protection of Scenic Vistas.

7. Efforts should be made, by conservation easement or fee acquisition, to protect the major scenic resources of the Park along travel corridors, with particular attention to the Adirondack Northway and those scenic vistas specifically identified on the Private Land Use and Development Plan Map and listed in Chapter III of this document.

Obtaining Right-of-Ways to Public Lands.

8. The acquisition of fee title to or rights-of-way across private lands that effectively prevent access to important blocks of state land should be pursued, except where such acquisition would exacerbate or cause problems of overuse or inappropriate use of state lands.

Obtaining Canoe water Right-of-Ways.

9. Canoe route easements should be purchased to reopen Adirondack canoe routes for non-motorized access in appropriate areas of the Park.

Obtaining Fishing Right Easements.

10. The highly successful fishing rights easement purchase program of the Department of Environmental Conservation should be continued and expanded on appropriate streams.

Avoid Purchases of Highly Productive Timber Stands,

Consider Conservation Easements for Timber Stands.

11. Due to the importance of the forest products industry to the economy of the Adirondack region, bulk acreage purchases in fee should not normally be made where highly productive forest land is involved, unless such land is threatened with development that would curtail its use for forestry purposes or its value for the preservation of open space or of wildlife habitat. However, conservation easements permitting the continuation of sound forest management and other land uses compatible with the open space character of the Park should be acquired wherever possible to protect and buffer state lands.

Adirondack Park Agency Prohibited from Reviewing Land Purchases Prior to Purchase.

While the Agency has not been given authority to review proposed acquisitions before title has vested in the state, once new lands have been acquired the Act requires the master plan to be revised by classifying the lands and setting guidelines for their management and use pursuant to the statutory procedures (consultation with the Department of Environmental Conservation and submission to the Governor for approval). The following procedures for revisions of the master plan will be followed in connection with new acquisitions:

— land acquisitions should be classified as promptly as possible following acquisition and in any case classification of new acquisitions will be done annually; and,

— prior to classification by the Agency, lands acquired by the Department of Environmental Conservation or any other state agency will be administered on an interim basis in a manner consistent with the character of the land and its capacity to withstand use and which will not foreclose options for eventual classification.

Adirondack Wild, Scenic and Recreational Rivers System

Today’s fodder is based on the text of the Adirondack Park State Land Master Plan that explains the Adirondack Scenic, Wild and Recreational Rivers System and the policies surrounding it quite well. — Andy

The Adirondack Park contains many rivers which, with their immediate environs, constitute an important and unusual resource. Classification of those portions of rivers that flow through state land is vital to the protection of existing free flowing streams. The classification system and the recommended guidelines specified below are designed to be consistent with and complementary to both the basic intent and structure of the legislation passed by the legislature in 1972 creating a wild, scenic and recreational rivers system on both state and private lands.

Definitions

A wild river is a river or section of river that is free of diversions and impoundments, inaccessible to the general public except by water, foot or horse trail, and with a river area primitive in nature and free of any man-made development except foot bridges.

A scenic river is a river or section of river that is free of diversions or impoundments except for log dams, with limited road access and with a river area largely primitive and undeveloped, or that is partially or predominantly used for agriculture, forest management and other dispersed human activities that do not substantially interfere with public use and enjoyment of the river and its shore. A recreational river is a river or section of river that is readily accessible by road or railroad, that may have development in the river area and that may have undergone some diversion or impoundment in the past.

Guidelines for Management and Use

Basic guidelines

1. No river or river area will be managed or used in a way that would be less restrictive in nature than the statutory requirements of the Wild, Scenic and Recreational Rivers Act, Article l5, title 27 of the Environmental Conservation Law, or than the guidelines for the management and use of the land classification within which the river area lies, but the river or river area may be administered in a more restrictive manner.

2. Rivers will be kept free of pollution and the water quality thereof kept sufficiently high to meet other management guidelines contained in this section.

3. No dam or other structure impeding the natural flow of a river will be constructed on a wild, scenic or recreational river, except for stream improvement structures for fisheries management purposes which are permissible on recreational and scenic rivers only.

4. The precise boundaries of the river area will be determined by the Department of Environmental Conservation, will be specified in the individual unit management plans for the river area or the areas, where the more restrictive guidelines of the particular area will apply) and with the following additional guidelines.

2. Access points to the river shore or crossings of the river by roads, fire truck trails or other trails open to motor vehicle use by the public or administrative personnel will normally be located at least two miles apart.

3. Other motor vehicle roads or trails in the river area will not be encouraged and, where permitted, will normally be kept at least 500 feet from the river shore and will be screened by vegetation or topography from view from the river itself.

4. The natural character of the river and its immediate shoreline will be preserved.

5. The following structures and improvements may be located so as to be visible from the river itself:

== fishing and waterway access sites;

== foot and horse trails and foot and horse trail bridges crossing the river; and,

== motor vehicle bridges crossing the river.

6. All other new, reconstructed or relocated conforming structures and improvements (other than individual lean-tos, primitive tent sites and pit privies which are governed by the regular guidelines of the master plan) will be located a minimum of 250 feet from the mean high water mark of the river and will in all cases be reasonably screened by vegetation or topography from view from the river itself.

7. Motorboat usage of scenic rivers will not normally be permitted but may be allowed by the Department of Environmental Conservation, where such use is already established, is consistent with the character of the river and river area, and will not result in any undue adverse impacts upon the natural resource quality of the area.

Recreational rivers

1. Recreational rivers and their river areas will be administered in accordance with the guidelines for management of wild forest areas (except where such rivers flow through wilderness, primitive or canoe areas, where the more restrictive guidelines of the particular area will apply) and with the following additional guidelines:

2. Where a recreational river flows through an intensive use area, structures, improvements and uses permitted in intensive use areas will be permitted, provided the scale and intensity of these intensive uses do not adversely affect the recreational character of the river and the river area.

3. The natural character of the river and its immediate shoreline will be preserved and enhanced.

4. The following structures and improvements may be located so as to be visible from the river itself:

== fishing and waterway access sites;

== docks;

== foot and horse trails and foot and horse trail bridges crossing the river;

== snowmobile trails, roads, and truck trails; and,

== motor vehicle bridges crossing the river.

5. All other new, reconstructed or relocated conforming structures and improvements (other than individual lean-tos and primitive tent sites which are governed by the regular guidelines of the master plan) will be located a minimum of 150 feet from the mean high water mark of the river and will in all cases be reasonably screened by vegetation or topography from view from the river itself.

6. Motorboat use of recreational rivers may be permitted, as determined by the Department of Environmental Conservation.

Designation of Wild, Scenic and Recreational Rivers

The application of the above definitions and criteria to rivers on state lands in the Park results in the current designation under this master plan of 155.1 miles of wild rivers, 511.3 miles of scenic rivers, and 539.5 miles of recreational rivers. A significant amount of private lands not covered by this master plan are included in these mileage figures. A brief description of these rivers and their classification is set forth in Chapter III.

| River | Wild | Scenic | Recreational |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ampersand Brook | 8.6 | ||

| Ausable — Main Branch | 21.7 | ||

| Ausable — East Branch | 8.8 | 25.2 | |

| Ausable — West Branch | 31.8 | ||

| Black | 6.8 | 5.8 | |

| Bog | 6.2 | ||

| Boreas | 11.4 | ||

| Bouquet | 42.7 | ||

| Bouquet — North Fork | 5.9 | ||

| Bouquet — South Fork | 5.0 | ||

| Blue Mountain Stream (Trib. of Middle Branch, Grasse River) | 7.9 | ||

| Cedar | 13.5 | 13.0 | 10.4 |

| Cold | 14.5 | ||

| Deer | 5.7 | ||

| East Canada Creek | 19.3 | ||

| Grasse — Middle Branch | 12.9 | ||

| Grasse — North Branch | 25.4 | ||

| Grasse — South Branch | 36.1 | 4.2 | |

| Hudson | 11.2 | 11.8 | 55.1 |

| Independence | 24.5 | ||

| Indian (Trib. of Hudson River) | 7.5 | ||

| Indian (Trib. of Moose River — South Branch) | 15.1 | ||

| Jordan | 15.7 | ||

| Kunjamuk | 7.1 | 9.1 | |

| Long Pond Outlet | 16.3 | ||

| Marion | 4.4 | ||

| Moose — Main Branch | 15.0 | 11.0 | |

| Moose – North Branch | 5.3 | 11.6 | |

| Moose — South Branch | 33.6 | ||

| Opalescent | 10.4 | ||

| Oswegatchie — Main Branch | 14.9 | ||

| Oswegatchie — Middle Branch | 13.0 | 22.7 | |

| Oswegatchie — West Branch | 7.2 | 6.3 | |

| Otter River | 8.8 | ||

| Ouluska Pass Brook | 2.3 | ||

| Piseco Outlet | 3.8 | ||

| Raquette | 36.0 | 51.6 | |

| Red | 8.0 | ||

| Rock | 6.4 | 1.3 | |

| Round Lake Outlet | 2.4 | ||

| St. Regis — East Branch | 15.4 | 6.3 | |

| St. Regis — Main Branch | 15.6 | 23.9 | |

| St. Regis — West Branch | 31.5 | 5.5 | |

| Sacandaga — East Branch | 11.3 | 12.6 | |

| Sacandaga — Main Branch | 28.5 | ||

| Sacandaga — West Branch | 18.1 | 16.6 | |

| Salmon | 11.6 | ||

| Saranac | 62.7 | ||

| Schroon | 63.9 | ||

| West Canada Creek | 7.4 | 17.1 | 9.1 |

| West Canada Creek — South Branch | 5.7 | 9.1 | |

| West Stony Creek | 7.4 | 7.7 | |

| Total | 148.4 | 487.2 | 545.6 |

Where to Camp in Black River Wild Forest

I have spent a lot of this past summer exploring the Black River Wild Forest, and decided it would be a good to share my experiences and some of the roadside and other campsites I’ve discovered along the way. As of September 2011, Lands and Forests in Albany doesn’t have these campsites in the central inventory, so all of this campsite data is based on personal exploration of these campsites.

North Lake.

Some of the best camping in the Black River Wild Forest is North Lake in Atwell. There are 22 campsites — many of them vehicle accessible along this man made lake. The southern end of the lake has some private houses and cabins on it, but it still is relatively pristine and beautiful. Most sites have outhouses and fire pits. Some but not all sites have limited wood supply. All sites designated.

Motors are allowed on this lake — as are on all wild forest lakes — so don’t be surprised to hear a jet ski or small boat on there. There are no public boat ramp on lake, so only hand launched boats can get on the lake.

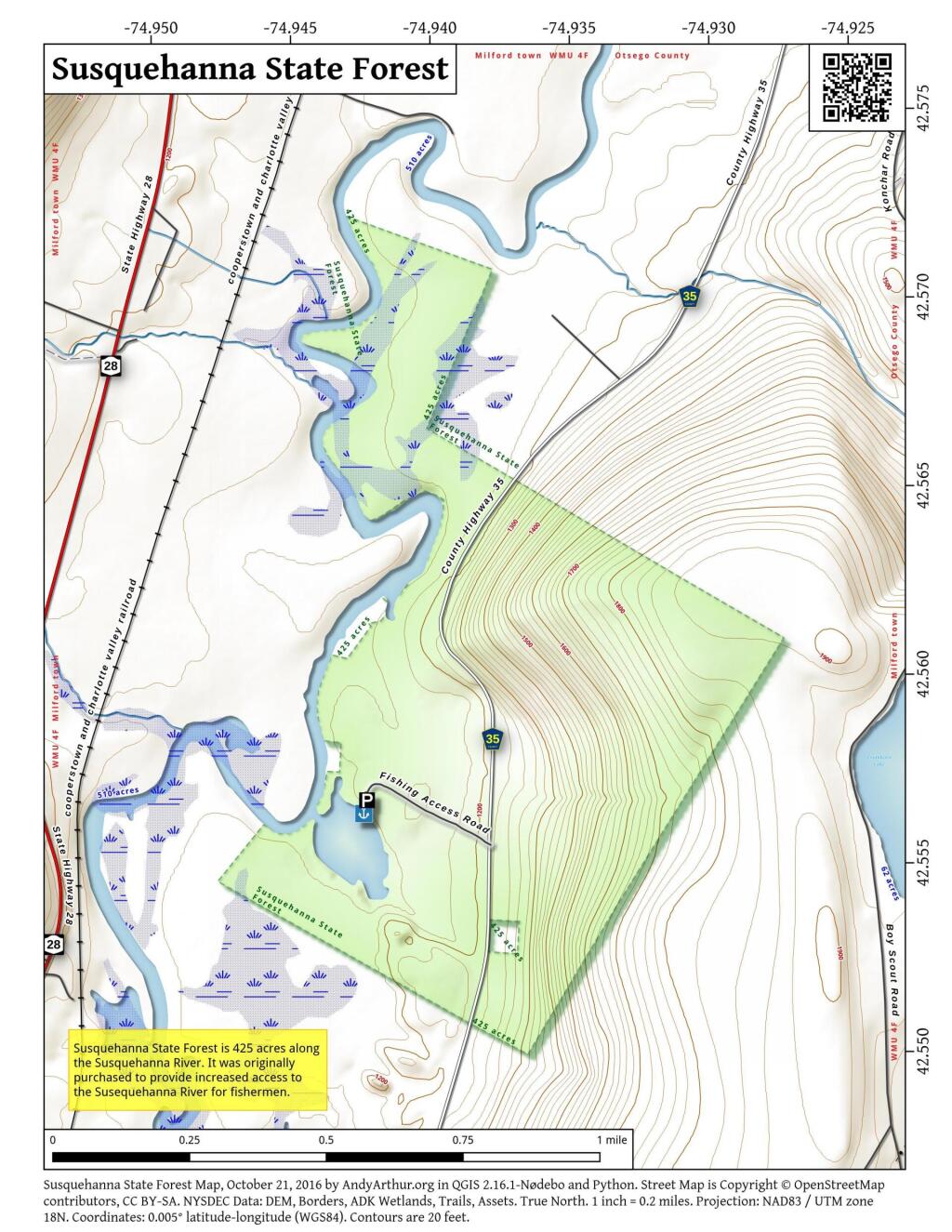

Click to download or print this map.

South Lake.

South Lake is another Erie Canal Corp / Black River Reservoir near North Lake. There is a single large campsite on South Lake, with a private in-holding on the other side of the lake. There may be other campsites here, as I didn’t explore this whole lake. There is an outhouse here, grassy field for camping, fire pit.

Click to download or print this map.

Reeds Pond.

There are a couple of campsites along Reeds Pond, North Lake Road, and Farr Road as you head up to North Lake from Forestport. This pristine, but relatively small pond is fairly popular for camping.

Click to download or print this map.

Wolf Lake Road.

There are 5 fairly remote roadside campsites along Wolf Lake Road, as you head down to Woodhull Lake. Note also how there are lean-tos at Bear Lake and Woodhull Lake. The roadside campsites have no facilities, and some can be muddy as they are not hardened with gravel.

Wolf Lake Road has recently been rebuilt and resurfaced with gravel, however spring rains did lead to one part that may lead low-clearance cars to bottom out. Camp on this road, and your unlikely to see more then 2-3 people drive by on any particular day.

Be aware that the last 1/8th of a mile to Woodhull Lake is gated, so you’ll have to carry your boat the rest of the way down to the lake.

Click to download or print this map.

Remsen Falls.

Remsen Falls, which probably should be called “Remsen Rapids”, is a popular swimming place, and offers two well used campsites. There is an outhouse and picnic table down here. The trail follows a gated dirt road.

Click to download or print this map.